Cindy Russell

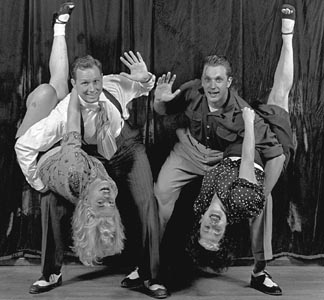

Fling Your Partner: Writer V. Vale's book celebrates the joy of swing.

To subcultural anthropologist V. Vale, the swing scene is the greatest thing since punk rock

By Michelle Goldberg

The first thing V. Vale did when I showed up at his office/apartment in a lovely little North Beach alley was to take my picture. Apparently he takes a snapshot of everyone who comes by and then keeps them, thousands of them, along with the oceans of books, videos, magazines, records, subcultural artifacts and files on subjects like "surrealism," "disasters" and "punk parenting."

I was thrilled to have my picture included in such good company. As one of the premier underground publishers of the past 21 years, Vale has interviewed many of San Francisco's most fascinating people. His books, which he calls "blueprints for emerging countercultures," have been the catalyst for many of the last two decades' most pervasive trends, including body-piercing and zine publishing. He began his career with a punk magazine called Search and Destroy, financed partly with $100 from Allen Ginsberg and another $100 from Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Later, with partner Andrea Juno, he started publishing Re/Search books, the most famous of which, Modern Primitives, introduced piercing and tattooing to disaffected youth nationwide. Today, minus Juno, Re/Search has mutated into V/Search. Vale's latest counterculture catalog, Swing: The New Retro Renaissance, will be out this May.

For the last decade, Vale's been waiting for the next big underground to come bubbling up. He's finally found it, he says, in the swing movement. As an outsider, I had always seen the swing scene as a kitschy nostalgia trip, but to Vale it's the most important countercultural movement since punk, an all-encompassing lifestyle with its own literature and aesthetics. In swing, Vale sees a thrilling grassroots rejection of consumer culture and planned obsolescence, an exhilarating reaction against grunge's drab nihilism, rock's three-chord tedium and the sexual hostility that has contaminated the '90s.

"As an old punk rocker who started publishing 21 years ago with Search and Destroy, I thought there would be a new youth revolution every 10 years, because that's what preceded me," he says. "The beatniks, then 10 years later the hippies, then 10 years later the punks. But then when it came around 1987, it didn't seem like anything happened. I was just waiting for something, but I didn't know what it was going to be."

What excites Vale the most about swing is its wild partner dancing. "It's so much fun! There's a joy. I've never known partner dancing as long as I can remember. I wasn't taught it. We're animals; we want to touch people. That's what I like about swing dancing. You don't have time to think how cool you are when you're dancing. If you did, you'd really fuck up. You have to be there in the moment. You feel really human. You really feel alive."

The Swing book comprises more than 30 interviews with swing musicians, dancers and scenesters from both the original '40s movement and its '90s incarnation, as well as sidebars in which each interviewee gives recommendations on music, magazines, movies and books. Also included are brief histories of local nightclubs that have been pivotal in the scene, including Bimbo's, The Deluxe and Cafe Du Nord. The people he interviews also see swing as an entire ethic. Some of what they say, though, can be difficult to swallow. Their attitude is more complex than conservatism, but there is a measure of longing for old-fashioned middle-class values in it, a disturbing sense that things just ain't what they used to be.

"People finally realize that the ads and computer graphics of the '80s really stunk. There are some things you can't improve on," says Michael Moss, publisher of Swing Time Magazine. A member of the leading neo-swing band Royal Crown Revue says that his dream when he first started playing the music was "to turn back time." Tanya Deason, wife of swing musician Vise Grip, inadvertently hints that the swing movement, in its postmodern way, is a rejection of modernism itself. "We're over the explosion of difference and 'originality.' " Over difference and originality? That's such a departure from any of today's most entrenched artistic values that it's almost impossible to figure out whether it's radical or reactionary.

What is undoubtedly refreshing is the movement's emphasis on conversation and civilization. "The one reason swing started in San Francisco rather than anywhere else is partly because Jay Johnson opened up this art-deco Deluxe on Haight Street," says Vale. "It was the first place where you could go for free seven days a week and sort of start a social movement. You can't start a social movement if you can't meet. Rock clubs, even indie rock clubs, do not foster conversation. The music is way too loud. It's really talking that starts social movements, rather than just going and listening to a band and then going home alienated, not having really met anyone at the show."

To outsiders, swing may seem like a flash-in-the-pan fad, but to devotees, their lifestyle signals the end of trends. Interestingly, much of their rhetoric echoes Baffler editor Tom Frank, who has consistently railed against our culture's obsession with hipness--interesting because Frank's bête noir has always been lifestyle politics. "There are few spectacles corporate America enjoys more than a good counterculture, complete with hairdos of defiance, dark complaints about the stifling 'mainstream,' and expensive accessories of all kinds," wrote Frank in an essay called "Alternative to What?"

The people in the swing movement agree with Frank. (Says local crooner Mr. Lucky, "Trends are marketing ploys, so corporations can keep pushing new 'product' for people to buy. Trends are just a way to sell stuff.") But their way of showing it is through, well, new music, new hairdos and a host of retro accouterments. According to Vale, there's no contradiction--since the swing movement worships the old, no corporations stand to profit from the scene's new styles. "I got a great deal of satisfaction from realizing that everything that was held up and exalted in this movement is all old. There's no way a corporation can make money on this. It's all been made, it's all from the past--the clothes, the furniture, everything."

Still, Vale and many of his interviewees readily admit that it's only a matter of time before corporations start producing '40s knockoffs. When they talk about that inevitability, their discussion switches to aesthetics. When I bring up the likelihood of mass-marketed swing paraphernalia, Vale replies, "Good. I welcome it as long as they're affordable. I like the aesthetic better. I think you can probably occasionally get something '40s-looking at the Gap, a dress for $40. That's people's prices. I would support that, because then you don't have to deal with all these smells that come from vintage clothes. I don't have anything against that as long as it fits the aesthetic. For now and for maybe quite a bit in the future, this aesthetic is what I've chosen."

[ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)