![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | SF Metropolitan | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copious Cubism

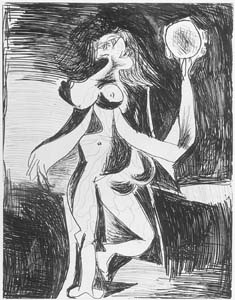

Art of the Times: 'Woman with a Tambourine' is just one of the many works by Picasso on view at the Legion of Honor Museum that reflect the encroaching threat of war as well as the artist's attempt to live a normal life during World War II.

Art of the Times: 'Woman with a Tambourine' is just one of the many works by Picasso on view at the Legion of Honor Museum that reflect the encroaching threat of war as well as the artist's attempt to live a normal life during World War II.

There's something wonderfully jolting about being in room after room of authentic Picassos By Christine Brenneman

Approaching the magically lighted Legion of Honor Museum on Oct. 9, music booms over the throng of yuppies in expensive black evening wear. In the museum's courtyard, I'm greeted by soft pink light and disco courtesy of the sequin-covered, big-haired singers of Big Bang Beat. Rodin's enormous Thinker silently holds court over this art extravaganza, and I head straight for the bar to loosen up enough to transcend the frantic mingling of this preview party and drink in the exhilarating art of Picasso and the War Years: 1937-1945. This event, hosted by Artpoint--the young professional members of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco--was designed to attract moneyed young people (read future donors) as well as much-deserved attention to this phenomenal exhibit. Even if you're not a big fan of the sterile environment of a large museum, this Picasso exhibit is well worth the trip to the outer Richmond. Anyone with a remote interest in art will thrill to the genius represented in these paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures. Covering the years surrounding WWII, the show explores Picasso's artistic response to the atrocities and horrors taking place in his native Spain and in the whole of Europe. In these tumultuous years, Picasso lived in France, and his work reflects the encroaching threat of war as well as his attempt to live a normal life. He made Paris his home during the four years (1940-44) of German occupation, and throughout this period, his work was a political and artistic protest against the war. Violence was everywhere in these years, fear was pervasive, and Picasso expressed this in his art with candor and passion. In his Weeping Woman (1937), Picasso lays bare the grief of war. Painted in a flat, fragmented Cubist style, this vibrant pink and green woman cries uncontrollably. Her face turns down in utter sadness, and in the dark background a tomblike black object alludes to the ever-present threat of death. In this moment, the woman represents all women and their bitter losses during the war. Continuing the theme of wartime casualties, Cat Eating a Bird (1939) shows raw barbarism. In this work, a monstrous and frightening gray cat attacks and rips at the bloody flesh of its prey. Here, Picasso effectively transforms a common domestic pet into a diabolical and cruel beast, a vivid symbol of the rough, senseless ferocity of war. Still, this exhibit is not without hopeful works. In his Bull's Skull, Fruit and Pitcher (1939), Picasso uses his signature style of fractured planes to depict a table laden with a pitcher, fruit and a bull's skull. The skull hints at death, but looking closer at the canvas, one notices a blossoming tree in the background, lush and full of life. This piece conveys the notion that nature and humanity can persevere in the face of death; the swirling orange of the pitcher, the pink blooms on the tree and the multicolored hues of the light coming in the window give this painting a joyous, high-spirited feel. Expressing the tumultuous moods of Parisian life in the shadow of combat, beauty, exuberance, death and agony jump off the canvas with equal force in the exhibit. Picasso imbues each piece with extreme emotion and a sort of fiery breath. There's something wonderfully jolting about being in the presence of a real Picasso. The viewer is confronted with room after room of important and stimulating canvases; it's like one orgasm after another for the art historian.

Films accompanying the Picasso exhibit give a complete picture of the artist's history.

Back at the Picasso preview party, it was amusing to talk to the patrons and party-goers about their impressions (or lack thereof). The funny thing about combining copious amounts of wine with art is that most of the pretense falls away and people actually feel free to say what they really think. Antonio, a civil rights lawyer from the South Bay, spent about five minutes looking at the exhibit. He then told me to email him after slyly slipping me his card, and soon after, he left to go find his "cousin." Yet another well-clad woman said, "We're getting a little bored faking our way through Cubism," and headed straight for the bar. One clearly more enlightened soul stated, "It's not hard to see that this guy [Picasso] was damn good at what he did." Indeed.

Picasso and the War Years: 1937-1945 runs Oct. 10-Jan. 3 at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Lincoln Park (34th Avenue and Clement St.). Adult admission is $12. Tickets are available at the Legion admission desk or through any BASS outlet; call 415/776-1999. The museum is open Tuesday-Sunday 10am-5pm with last admission to the exhibition at 4pm. The exhibition will stay open until 8:45pm every Wednesday night, Oct. 14-Dec. 30. Last admission on late Wednesdays will be at 7:45pm. Wednesday evenings after 5pm and second Wednesday of the month regular admission fee is waived-Picasso special exhibition fee still applies; admission for all, $5. For more info, call 415/863-3330 or visit the Web site.

|

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()