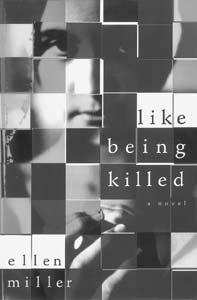

Junkie Lit: Ellen Miller's stunning debut novel, 'Like Being Killed,' is a caustic story of a junkie and her relationship with her roommate.

Junkie Lit: Ellen Miller's stunning debut novel, 'Like Being Killed,' is a caustic story of a junkie and her relationship with her roommate.

Junkie literature is often insufferable and occasionally brilliant

By Simone Stein

It's easy to laugh at the spate of heroin literature that publishers have churned out in the 1990s, self-indulgent tales of young white people on junk that decorate bookstore shelves with their gritty-but-slick covers. In fact, to say that some of these books are stories of hipsters on smack is a misstatement, because many of them are about drugs first, characters later. The protagonists of books like Linda Yablonsky's The Story of Junk (a semi-autobiographical novel which could have been called "My Friends and I Were So Damn Cool") and Peter Trachtenberg's memoir 7 Tattoos are blanks, worth writing about only because of their authors' penchant for illegal substances and not-as-transgressive-as-they-think lifestyles. Both aim for some kind of universality that gets lost in affectless prose and numbing cycles of copping, shooting, kicking and complaining. (Except, that is, for one hallucinatory passage in 7 Tattoos about a chapel for junkies, a scene so eerie and beautiful it seems to be from a different book.)

But junkie lit can't just be written off as the cultural production of people who took heroin chic way too seriously because, for all the dull drug books, narcotics have also inspired much of the decade's most stunning, searing writing: Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting, Richard Hell's Go Now, Jerry Stahl's Permanent Midnight, much of David Foster Wallace's The Infinite Jest and, recently, Ellen Miller's stunning debut novel, Like Being Killed.

Like Being Killed is the story of a brilliant, caustic, masochistic Jewish junkie named Ilyana Meyerovich and her fraught relationship with her wholesome, maternal roommate, Susie. There are moments in the book that are more brutal than anything imagined by William Burroughs, because the characters being abused are people the reader identifies with, not just the anonymous bodies that swing mutilated through Naked Lunch like something out of Bosch. Some of the hideous sexual violence between Ilyana and a nameless plumber is so disturbing it can be hard to keep reading. But there are also scenes full of an almost religious compassion, and the whole novel resonates with moral complexity and philosophical struggling. Miller puts Ilyana's addiction into a context of centuries of philosophical and mythological thought about hedonism, nihilism and existentialism. Her writing is suffused with visceral suffering, crystalline intelligence, black-hole humor and stunning flashes of grace.

So why do opiates inspire young writers like no other drug? Maybe it's because heroin is one pastime that can't be discarded as easily as love or politics or partying. Obsessive romance now seems either scary or absurd--it's probably no coincidence that love, in these books, tends to be a sadomasochistic farce. In contemporary literature, any pretense to overriding conviction is often just a ridiculous pose. A book like Doris Lessing's The Golden Notebook, a devastating novel about a writer's tortured addiction to the Communist Party, could never be written today, when the only thing socialist iconography is good for is Taco Bell commercials and vodka ads. Heroin, though, gets its claws into a narrator and won't be dismissed. "I was so in love," writes Hell. "Dope was so magic. We were Romeo and Juliet. It was just what I'd always wanted without even knowing it, stuff that lets you not only dream while awake, but gives you the power to prod and stroke and sculpt the dreams, introduce action and characters--to direct your own dreams. And dreams are just another form of being awake. With junk you can dream your life."

Heroin is also a quick route between slumming middle-class kids and the underworld, and addiction is likely the most intense suffering that privileged people ever will experience. This points to a strange coincidence among recent heroin books: a number of their protagonists are the well-off children of Jewish immigrants who were victims of the Holocaust or European pogroms. In The Story of Junk, 7 Tattoos, Permanent Midnight and, most, explicitly, Like Being Killed, there's a brooding sense of guilt by second- or third-generation Jewish immigrants throwing away their family's hard-won middle-class gains, along with a weird sense of inevitability. Copping on the Lower East Side, Yablonsky's narrator says, "My mother grew up in a Second Avenue tenement; my father was born on Avenue D. I'm just going back to my roots." Writes Stahl, "You can imagine how proud I am: Dad was an immigrant made good as a public servant; son's a drug-taking pornographer."

Miller, though, is the most explicit about the special self-destructive guilt of children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. "Primo Levi wrote that if one message could have seeped out from Auschwitz to free people, the message would urge people not to suffer in their own homes what was inflicted upon prisoners there, in Auschwitz. ... I was doing exactly what Primo Levi had warned against: bringing into my own home what was inflicted upon people who looked like me in a catastrophe that might have been mine. The world I chose to inhabit now had appropriated a history of suffering and slaughter that I despised strenuously but of which I had become an instrument."

None of these writers are crass enough to compare their ordeals to concentration camps. On the phone from Manhattan, Miller described Ilyana's conflating of her addiction and her Holocaust obsession as "her own private little Stockholm syndrome, a sort of romancing the things that you know to be hell." In Like Being Killed and Permanent Midnight, heroin addiction is the culmination of years of generational destruction; it is, as Miller says, "the how, but not the why." Similarly, in Trainspotting the why is the no-future desolation of blue-collar Scotland. Heroin's just an agent.

Not that these books are cringing morality tales--Trainspotting and Go Now are alive with the pleasures of drugs, and many of the characters in Trainspotting make a case that narcotic joy is the only kind they're likely to find. But what separates the brutal, beautiful books about heroin from the trendy, self-pitying ones is the sense that drugs are neither the beginning nor end of the story. Says Miller about Like Being Killed, "This is a book about a fall from grace. What I was trying to show is what we call a state of grace, which in the book was this friendship, already contains the seeds of its own destruction. The grace contains the fall, and the fall contains the grace. If this book was only about the fall, 'I did more drugs and then I did more drugs and then I did more drugs,' so what?"

In Naked Lunch, William Burroughs writes, "Remembering a period of heavy addiction is like playing back a tape recording of events experienced by the front brain alone. Flat statements of external events. 'I went to the store and bought some brown sugar. I came home and ate half the box. I took a three grain shot etc.' Complete absence of nostalgia in these memories." Perhaps that explains why books that are just about heroin can be so flat, so affectless. Yablonsky writes, as if to explain the odd weightlessness of her own novel, "There's no way to excuse or explain it. The whole story of junk is a song and a dance. Everyone's got a story to tell, and most of those stories will change in some way, every time they're told. Not this one, not the story of junk. This one's always the same." That could be why books whose only story is junk are ultimately so monotonous.

Complex, rich books do try to explain things. "Some of the literature that deals with people like Ilyana is concertedly nihilistic, concertedly cool, affectless," Miller says. "I find that tendency toward affectlessness troubling. I remember from math in elementary school that there was a difference between zero and the null set. If you have a piece of white paper in front of you, that's not nothing. I don't think anyone gets affectless for no emotional, ontological reason. For me, that's the difference between zero and the null set, between nothingness and an overwhelming sense of lack."

Miller continues, "On the one hand, there's a conservative dimension to the way the culture demonizes drugs--'Just Say No,' which is to say, 'Don't contemplate, don't wonder, don't think.' But there's also an equal and opposite tendency among the people who eschew that first view, which is to make drugs some kind of sacred, idealized experience. Both of those are dangerous. They both strip the individual of her humanity. No one's life is so small that it can be reduced to a drug."

[ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)