![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Neurotica

Laying Bait: Will the descendants of 'Bridget Jones' ever catch a man?

Laying Bait: Will the descendants of 'Bridget Jones' ever catch a man?

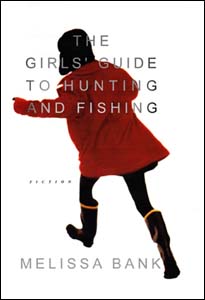

Does the latest batch of savvy chick lit stem from emancipation or desperation? By Irina Reyn The literary world, we are told, is in the midst of a phenomenon: breezy books written by thirtysomething successful single women about thirtysomething successful single women living wild in the big city. It all seemingly began with Helen Fielding and her wildly popular Bridget Jones' Diary, which paved the way for books aimed at women haplessly looking for love while juggling a career. It was OK to be in your 30s and still single, Bridget Jones made clear, and to stay in watching television on a Friday night, cheerfully avoiding "smug marrieds." Despite some critical backlash, however, the juggernaut to reckon with this summer is Melissa Bank's The Girls' Guide to Hunting and Fishing. The book consists of interlocking stories following the life of New Yorker heroine Jane Rosenal from her teens to her 30s. It is not thoroughly seamless, however. Several chapters are out of sync with Jane's first-person narrative: one is told from the perspective of Jane's neighbor, Nina, and the other from the third-person perspective of a young woman going through cancer treatment, after which she breaks up with her boyfriend. The chapter related from Nina's sudden perspective is perplexing and not justified--its presence among the other flowing tales is jarring. We follow Jane's growth into womanhood with avid interest. The strongest chapter is the first, "Advanced Beginners," in which a teenage Jane is for the first time faced with the reality of relationships, through her brother and his girlfriend, Julia. At first intimidated by Julia's intelligence and class, she soon begins to admire her and sets up their relationship as a possible prototype for her own future ones. When the relationship ends, she is heartbroken and wiser: "I didn't know what happened between him and Julia. It scared me to think that my brother had failed at loving someone. I had no idea myself how to do it." The crux of the novel is Jane's relationship in her 20s with an older man, a famous book editor--perhaps modeled after Jonathan Galassi of Farrar, Straus & Giroux--who teaches her the pain of adult love. Although rendered with realistic grace, the relationship seems a bit improbable, more from her side than his. At one point the editor, Archie Knox, calls Jane "a blurry young person" and in a sense she is. We are constantly in her head without really knowing her. However, we feel affection for her, with her knowledge of her own limitations and her often hilarious discernment of the situation at hand. Interestingly, literature swirls around Jane throughout the book. Her brother and Julia worked in publishing houses, she herself is in the editorial department of a publisher and Archie is a famed editor of important fiction. Yet literature has no real resonance in this novel. Jane remains self-deprecating about literature as well, as though she is uncomfortable in the role of literary sophisticate. The same could be said for Bank, who is a brisk writer with a fine-tuned sense of humor. Her final chapter, the title story, is a well-crafted comedic piece about the two imaginary authors of a Rules-type book dictating to Jane how to keep the man she met at a wedding interested. Despite its eye-twinkling humor, this story feels too well honed and structured, all craft and little substance. Not surprisingly, this is the piece first published in Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope, which snagged Bank her six-figure deal from Viking/Penguin Putnam and generated all the hype. Still, Bank's is the best of the "single girl" fictions on the market. The earliest of them, Animal Husbandry, by former Knopf publicist Laura Zigman (Delta Press)--now in paperback--presented the Darwinist approach to dating with New York television producer Jane Goodall coining the not-very-flattering terms of "New-Cow" and "Old-Cow." Despite the compulsive readability of this gimmicky novel, the reference to the seemingly inevitable downgrade from girlfriend to ex-girlfriend is a bit simplistic if not downright insulting. Melissa Roth's journalistic effort, On the Loose: Big City Days and Nights of Three Single Women (Morrow), chronicles the lives of three women with impressive jobs living in important cities. Unfortunately, Roth cannot stray from the topic of their dating lives--so much that when one woman suddenly quits her job, it comes as a surprise, since her frustrations at work are barely mentioned. And for all the Bridget Jones fans who assume that bliss is guaranteed once the engagement ring is safely ensconced on the single girl's finger, along comes Otherwise Engaged by Suzanne Finnamore (Knopf), which quickly repudiates the notion. Eve, a 36-year-old ad executive, finally gets her live-in boyfriend to propose. Once the time spent on this man is vindicated through the wedding ring, Eve develops acute anxiety, and as she stumbles through the story she veers between humorously neurotic and extremely annoying. Once again, character development is sacrificed for a wry perception of life. It is a bit unfair to lump these books together as cotton candy for the Ally McBeal crowd. It also may be a bit hyperbolic to consider the influx of these books as a portent of a new cultural trend. However, they should not be disregarded, if only for the undeniable glimmer of insight that permeates certain passages. "I don't write to instruct," said Terry McMillan, the author of Waiting to Exhale, who novelized the issues of single women well before Bridget Jones started complaining about her single status. "I write to understand, to make some sense out of things." If these books have helped make any sense at all out of modern relationships, they have performed a valuable service indeed . [ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the July 19, 1999 issue of the Metropolitan.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.