![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Celebrating Selling Out

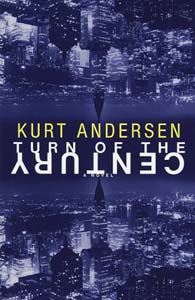

The Way We Will Be: Andersen's gentle satire of the bicoastal elite.

The Way We Will Be: Andersen's gentle satire of the bicoastal elite.

'Turn of the Century' is an epic for aspirants Kurt Andersen's epochal Turn of the Century may be the first contemporary novel to treat bicoastalism as a true neurotic disorder. A sweeping, deeply engaging story of people caught up in the media-technology-entertainment vortex, Turn of the Century is alternately a scathing satire of and a sympathetic comedy about clashing values in New York, L.A., Seattle, Silicon Valley and Las Vegas. There's a special relevance here for the kind of guilty aspirants who teem in our city: professionals suddenly making more money than they ever dreamed possible, negotiating opposing currents of greed and ethics and finding that they enjoy being the kind of people they once despised. Andersen's characters, globe-trotting lapsed liberals all, seem constantly plagued by the fear that they're somehow not in the center of things, both metaphorically and geographically, largely because in the world of the novel there is no center anymore. That world is like ours, only a tiny bit more so. Set in the year 2000, Turn of the Century amps up the absurdities of the present half a notch or so--there's a Las Vegas hotel called Barbie World and a prime-time TV program, Finale!, devoted to celebrity obituaries. Glossy magazines and catalogs have begun merging into magaloges and the moviephone guy has his own TV segment. Our protagonists are George Mactier and his wife, Lizzie Zimbalist, happily married and complacently rich Manhattanites. George, after a laudable career in journalism, has gone to work in television producing and found he quite likes being a player; Lizzie, a Harvard MBA, is negotiating a very lucrative deal to sell her technology company to Microsoft. It's immediately obvious that their somewhat smug security can't last. Indeed, their whole lives seem like targets for a Tom Wolfe-style onslaught of humbling tribulations. But while Turn of the Century is already being compared to Bonfire of the Vanities, Andersen, himself a consummate yuppie insider (he's a writer for The New Yorker, a co-founder of Spy, a former editor at New York and an occasional TV producer), likes his characters too much to really want to take them down. Thus the Wall Street titan here, Ben Gould, has a secret heart of gold, buying up the rights to novels that he loves in order to save them from being made into movies and making anonymous million-dollar donations to methadone clinics and soup kitchens. George and Lizzie don't have affairs, they only suspect each other, leading to almost tragic misunderstandings and near-nervous breakdowns, most resolved via exhilarating plot twists rich with rueful warmth. Indeed, Andersen's hilarious venom is directed more at the infotainment industry itself than at those caught up in it, even when they become utterly corrupted by it. As the book begins, George is working on a new-entertainment hybrid seemingly custom-designed to give Steve Brill conniptions. Called Real Time and starring real news anchors, the show is a thrice-a-week soap opera about television reporters that culminates in a real newscast with real stories, thus furthering the dissolution of the line between fiction and reality. Although the show nearly destroys George's career, it's not for the reasons one would expect-indeed, Andersen forces us to empathize with him, since his enemies are even more craven. That's precisely the reason Turn of the Century will infuriate more earnest readers. The novel is nearly unflinching in its embrace of yuppie values. "They care with equal and dazzling Bessemer passion about the monumentally unimportant--about living on the correct side of the correct street in the correct latitude of the correct neighborhood, about sitting at the best table at the best hour at the best restaurant, about wearing the right shade of indigo, thickness of sole, expression of sangfroid," Andersen writes. "Lizzie likes to think she has moved beyond automatic scorn or pity of this strain of bicoastal madness. She has begun to see all the Bel Air and Park Avenue wanting as a perverse romanticism, vanity and self-advancement pursued so monomaniacally that they turn inside out and become a kind of naiveté, the naiveté of children." This tempered endorsement of elitism will likely grate on those who don't recognize it in themselves. For those who do, however, it seems like someone saying a guilty secret out loud. In that sense, Turn of the Century is highly self-congratulatory, meant to flatter readers who relate to its characters, which is precisely why it is so satisfying. Like money, ambition is a kind of taboo, especially around here, where the air is thick with it but everyone pretends to more concerned with other, deeper things. For those who've never wanted to be powerful, trendy or famous, God bless them, Turn of the Century will likely seem terribly frivolous. But for those whose desire for those things is blind and surging (and a little shameful), and who struggle to reconcile such lust with basic decency, Turn of the Century is delicious, gourmet comfort food for slightly corroded souls. [ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the June 7, 1999 issue of the Metropolitan.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.