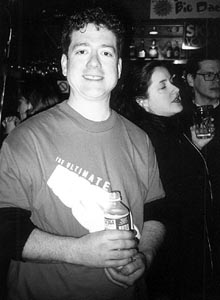

Advertising Attire: Joe Quirk, author of the roller-blading thriller 'The Ultimate Rush,' sports a fluorescent orange promotional T-shirt at his book party.

Advertising Attire: Joe Quirk, author of the roller-blading thriller 'The Ultimate Rush,' sports a fluorescent orange promotional T-shirt at his book party.Matt Ipcar

Author Joe Quirk is poised to become a literary sensation--too bad his book is awful

By Michelle Goldberg

In an age when some mid-list writers can't get their publishers to finance a book tour, first-time author Joe Quirk is being lavished with publicity for his San Francisco-based roller-blading thriller The Ultimate Rush. In addition to a full-page New York Times ad and a clever email campaign, a few Fridays ago his handlers planned to have 200 roller bladers wearing fluorescent orange "Ultimate Rush" T-shirts meet Quirk after a bookstore appearance and escort him to a "pep rally" in front of the Ferry Building at Market and Embarcadero. From there, they planned to proceed to a party at the Marina's Triangle Lounge, where bartenders, also clad in promotional attire, would dole out free Skyy vodka drinks.

Alas, a frigid rainstorm foiled all the festivities except the party. It was as if some outraged literary god was making a stand against this latest devolution in the world of letters and trying to prove that nature can still trump hype.

You see, while Joe Quirk, The Ultimate Rush's 31-year-old author, is charming and likable, the book is phony in the most luridly Hollywood high-concept way. This tale of a punk-rock computer-hacking roller blader named Chet Griffin and his blue-haired riot-grrl sidekick battling the Chinese mafia and the San Francisco Police Department reads like a 354-page Mountain Dew commercial. It abounds with cringe-inducing dialogue such as, "Chet, much as the street surfer in me wants to admire your utter hypeness, as your chum I have to say that is totally the boneheadedest thing you've ever done--and that's saying a lot, for you." Additionally, Quirk has jettisoned such ordinary phrases as "he said" and "she said," preferring to keep it real by using "He's all" and "I'm like" and "She goes," as in "He's all, 'Why should I relinquish the scepter of power?'" or "I'm like, 'Hey, this is a 'temporary lapse' in my studhood.' "

The plot is propulsive, though predictable, and Quirk is occasionally quite witty--Chet's love interest and partner in crime is named Ho after Ho Chi Minh, her hippie parents never predicting that "the word 'ho' would soon adopt even more nefarious connotations." But unlike writers like Irvine Welsh, who know how to nail sub-cultural slang and make it sing, Quirk creates characters so earnest in their embodiment of Gen-X stereotypes that it's almost painful to read. Quirk is to Welsh what Third Eye Blind is to The Stooges.

When I was midway through the book, a co-worker asked me how it was. I told her that it read as if the author had used one of those cheesy paperback dictionaries of slacker lingo. Amazingly, when I talked to Quirk the next day, he told me that he used a "hacker dictionary" that he got from the library to construct his characters and that he never even sent his first email until after he finished the book. Now, Quirk can be applauded for ignoring the misbegotten advice to "write what you know," a dictum that has surely led to the current glut of solipsistic memoirs. But he should at least have made an attempt to become as familiar with the Internet as the average reader, who is well over Wired-style Web euphoria.

Then again, Quirk has a way of pre-empting criticism of the book. He admits right up front that most of the slang is outdated, saying, "I don't think slang shouldn't be used in literature just because it changes. Maybe 18-year-olds will know it's dorky, but 30-year-olds will say, 'Oh, cool.' " At his book party, he appeared a bit dazed by all the people hugging him and congratulating him. He looked devious, weary and amiable at once, and though he's over 30 he could pass for 21.

He doesn't bristle when I ask him whether young readers will be turned off by the aggressive marketing for the book. "It is an irony," he said. "Chet is really big on not selling out, and yet he's represented in a book that's represented by powerful forces. It all depends on the type of powerful publishing house you're with. The really cool thing about Rob Weisbach books is that they're taking chances with new, young and predominately gay writers and putting major marketing power behind them and presenting them as mainstream. ... He's a young guy, and he came into the publishing industry and shook things up and changed it for the better."

Many readers and writers would disagree with that--Weisbach is, after all, the man who signed Whoopi Goldberg, Paul Reiser and Ellen DeGeneres, giving Goldberg a reported $6 million advance. "Some people think that when you put a lot of publishing money into Whoopi Goldberg or Paul Reiser, it takes money away from real writers," Quirk says. "With huge publishing houses that's probably true, but in houses with a small number of titles, they put out people like Whoopi Goldberg and make a whole hell of a lot of money, and that allows them to put money behind more risky stuff."

Well, not quite--Goldberg's book sold notoriously poorly. But Quirk's point still makes sense--it is good to have a publisher willing to take risks on young unknowns. Quirk has received 375 rejection letters since he started writing, so one wants to root for him, the little guy triumphing over the stodgy book world. An editor at Harper's, according to one article, even wrote, "Give it a rest, pal," on the bottom of one refusal. Such persistence in the face of discouragement is the stuff that literary history is made of, except for one thing--in this case, the nasty editor was right.

[ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)