![[Metroactive Features]](http://metroactive.com/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Suburban Dreams

Photo by Del Carlo Living Made Easy: Bohannon's Westwood subdivision, built over five years, promised buyers not only a house, but a chance to grab hold of the American Dream: home ownership, kids playing in the yard, friendly neighbors. Despite the agonies of a Saturday drive down Stevens Creek, personal peace, community and a way of life still endure in the oldest suburban housing tracts of the valley. Frank Lloyd Wright would be proud. By Jim Rendon JUANITA DRIVE BENDS gently as it passes Bert Martin's Santa Clara home, merging in an arc with Bohannon Drive, which twists into the tree-lined distance like a whimsical melody in a Frank Sinatra song. The little houses, watched over by towering sycamore trees, are small, safe, perfect--a scene painted on a cake. From the street Martin's home is barely distinguishable from his neighbors'. Some have peaked shake roofs, others have been updated with composite shingles, a few have a small gable over the garage. A few pale colors are all that really differentiate one house from the next. After nearly five decades as a community, there are surprisingly few additions visible from the street in this neighborhood: a handful of second stories and one or two sprawling monsters just out of view around the corner. Standing in his yard, abutted by fences around five different homes, Martin, a short, fit 74-year-old, squints against the sharp spring light. His blue eyes light up as he points out the line of the roof over his open-air patio. "A square, there's nothing about it. No artistic design to it," he says. "We wanted our back yard to be different. When you step in, your eye should sweep across the yard and catch things, like when you look at a painting, beginning on the left and sweeping across that way," he says, gesturing around to the other side. Martin is a Liberace fan who once went to see the glitter-bound performer at the now-razed Circle Star Theater in San Carlos. That's why, in the spring of 1954, Martin sat down with paper and pencil and began to design. He bought lumber and a wheelbarrow and went to work. Soon, he had a cement patio where before there had only been a tiny square slab. The result is that each section radiates out from a central point, like a series of sunbursts. The sweeping roof that caps the patio, providing shade against the hot Santa Clara summer sun, was hoisted up on posts that year, cobbled together in the shape of Liberace's open piano lid. Ducking in from the sun, Martin grabs his tan, floppy sun hat and his cordless phone as he makes his way out of the garage, along his fence and out onto the street. Martin shuns the sidewalk for the broad empty road that separates the single-story pastel houses from each other. As he walks through the neighborhood, Martin slows to point out the homes of his friends, changes in the yards. He pauses in front of one whose owner has passed on. The house is now sold, and the yard is falling into patchy-brown disrepair. Martin has lived with the tract dwellers in one of the valley's first suburban housing tracts for nearly half a century. And over the decades, they have grown into a community here. But that's not too surprising. Like partners in any good relationship, they had a lot in common from the start. "We had all just gotten out of the service," Martin says. "We all wanted to see better things, and we came here and thought, 'Now we can conquer the world.' This place gave us a chance." Martin and his neighbors in Santa Clara's Westwood subdivision were the early pioneers in a new way of living that, for better or worse, has become the cornerstone of American culture and the second most famous attribute of Silicon Valley. While "suburbs" have been around so long that the Caesars complained about their proliferation outside Rome, the post-World War II housing tracts like those in Santa Clara are different. Until World War II, suburbs were a semi-rural extension of the city relying on the urban center for economic survival and cultural life. The suburb was wholly dependent on the city, providing its wealthy residents a bedroom respite from the poverty and dislocation of Industrial Revolution- era cities. Developments like Westwood that sprang up in the valley following the war marked the beginning of something new. When Martin's neighborhood was built between 1951 and 1953, he fretted for months that he had moved too far out in the country. There were only a few other housing developments in Santa Clara, a city with a population barely over 10,000. Separated by miles of orchard from San Jose, floating in its own isolated universe, the subdivision bound itself to the rest of the world by roads traveled by cars. Unlike trains that connected earlier urban expansion to the city's core, cars could go anywhere a road took them, around the corner or to the other side of the bay. The development depended on no single place for its economy, for its entertainment and culture. Martin owned a body shop on Market Street in San Jose. But he also opened a used car lot on Stevens Creek in Santa Clara. One neighbor inspected ships in San Francisco. Dick Pefley, in a cream-colored home just around the corner from Martin, bicycled to and from work at Santa Clara University. Westwood, hammered together by developer David Bohannon in the midst of a prune orchard, marks the beginning of the modern Burb. EVERY WEEKEND DURING the fall of 1952, Bert and Helen Martin drove from their rented apartment on East St. James Street in San Jose to a little plot of land in Santa Clara to watch their house rising in a field of prune trees. As the roof went up and walls materialized, they watched their neighbors move in. Then, in early 1953, it was their turn. Spring was hot and windy that year. Everyone on Juanita and nearby Bohannon was struggling to get lawns started. When they bought Bohannon's houses, they were just that: houses on a dirt lot with a square cement slab in the back. Prune trees still dotted most of the lots. After seeding the lawn, Helen covered it with peat moss to protect the seed. Every day the damp peat moss would dry in the sun and blow away. "It was so awful," she remembers. "I was so glad to see the seeds germinate so I wouldn't have to be out there keeping it wet." Kneeling on their lawns, new neighbors got their first glimpse of each other. "You really got to meet people when you were outside putting in the yard," Helen says. "And when you have kids, you meet everyone up and down the street." It was almost a year before the fences went up in the backyards, something that Helen, who grew up on a vineyard in Hollister, had a tough time with. "I lived on a ranch. I was used to seeing open spaces. We had barbed wire, because of the cows, but nothing like this." But when the fence posts were set, there was little argument. Like the lawns in front, fences in the back were just another part of this new life in the Burbs. Bert, who was trying to get his new body shop off the ground, worked six or seven days a week. Late nights were the norm for him and many of the other men on the street. "I saw my family grow up at night. The ladies saw each other in the bridge club. The fellows saw each other mowing the lawn in the evening." Helen became absorbed in the Girl Scouts and the PTA. What little time was left was spent doing the paperwork for Bert's auto body shop. After work, Bert served on the Planning Commission and led a failed battle to stop the proliferation of second-story additions. Today, neither can imagine how they got it all done. Around the corner from the Martins, Vern and Margaret Wyman were also getting settled into their own home. While Vern worked at the assessor's office in San Jose, his wife, Margaret, carpooled once a week with other women to go shopping. Most families were one-car operations back then, and the car went to work with the men. The closest market was two miles away on the corner of Stevens Creek and Winchester. After settling in, many of the women in the neighborhood started getting together once a week to play cards. "We paid a woman 50 cents apiece to teach us how to play bridge," recalls Wyman. "We had gotten tired of playing canasta." Forty years later, they still meet for cards.

Commuter Crunch: While unplanned decentralized suburbs are often maligned for causing traffic disasters, Dick Pefley, who bought his home in 1953, bicycled to work every day for decades. DEVELOPER David Bohannon spent a lot of time in the 1950s driving through orchards and open fields in the Bay Area. He wasn't looking for fruit stands, he was looking for land. "He did what builders today do," says Frances Nelson, Bohannon's daughter and now president of Bohannon Development Company in San Mateo. "He searched for a mature orchard operation where the owner was old enough and wanted to get out of business, or where there was no family to take over the business. He was looking for farmers willing to sell their land for housing," she remembers. Then she pauses. "A lot of people feel as if that was evil. I think it was sort of inevitable." The year 1950 was a turning point for the city of Santa Clara. Throughout World War II, agriculture had thrived in the valley because the rich soil and abundant water made farming lucrative. As the postwar economy picked up, California towns were flooded with vets just home from the war ready to take advantage of cheap government housing loans. Farmers could suddenly make more money by selling property to a developer than they could working the land, says Fred Carlson, a former senior planner in Cupertino. On May 14, 1951, Bohannon paid Peter and Matthew Talia $235,000 for their 68-acre prune orchard near the intersection of Newhall and Saratoga in Santa Clara. The subdivision, one of the first in Santa Clara, was a big step, bringing $4 million worth of homes to the tiny city. Part of the agreement was that Bohannon put off construction until after that year's harvest was brought in. All across the county similar developments were under construction. Between 1949 and 1950, the number of homes built in the county nearly doubled, from 4,300 to 8,300. In 1954, the number jumped again from 6,300 to 9,900. Sears abandoned its San Jose store on South First Street in 1953, settling instead for a more suburban location on San Carlos Street. Valley Fair shopping center opened in 1956 to serve new developments like Sunnybrae in Santa Clara, Rancho Rinconada in Cupertino, Sunnyvale Manor, Los Altos Rancho and countless other developments rising from the fruit orchards of Santa Clara County. By the time Bohannon set his sights on the South Bay, he was already a successful builder, with decades of construction under his belt. Though Bohannon's father edited California's first socialist newspaper, the young man had his eye on money and power early on. He dropped out of school at age 13, and just a few years later at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco, Bohannon ran a sightseeing concession where he guided Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and former President Taft through the exhibits. In 1933, at the age of 35, Bohannon built his first homes in Menalto Park in San Mateo. Working on those early homes, Bohannon gained a respect for quality construction, his daughter says. "He got spoiled. The men he hired for the first project were highly skilled journeymen that turned out beautiful stuff. I live in one of those houses now," Nelson says of her Peninsula home. In the rush to provide housing for returning GIs, Bohannon lobbied the government to turn home construction over to private companies. In the process, he met influential developers, including William Levitt, who built Levittown, America's best-known early suburban development. Bohannon learned a lot from his colleagues. "He would have a half dozen, maybe more, different facades or finishes or fronts of houses so these were not identical homes, so there was enough variation in plan to make an attractive neighborhood," Nelson says. "We prided ourselves in providing a plan for a school, library and retail areas. A balanced community was always important." While it took decades for many of these amenities to take form near Westwood, Bohannon did build Westwood Elementary School as well as a small park, additions that helped Westwood coalesce into a neighborhood. When more developers began combing the fields for bargains and slapping up quick, inexpensive homes, Bohannon got priced out of the market. He could no longer compete building the high-quality houses he had come to expect. Instead, he opted out and turned to commercial development, Nelson says. AND SO TODAY, much of Bohannon's work is still standing, largely intact, filled with a surprising number of original homeowners. Under the shade of a towering tree on Bohannon's namesake drive, Dick Pefley is raking up the last of his lawn clippings and stray leaves. A lush deep green, bordered by flower beds and a manicured walkway, Pefley's yard, like those that surround it, beams with care. Pefley's home sits on what by today's standards is a giant pie-shaped lot. Behind his house, a bag half-full of oranges that have fallen fresh from the tree lies on its side in the shade. Flowers and shrubs grow a little more free. A half-completed garden plot dries in the sun against the back fence. Though hardly neglected, it feels more wild, more practical than the perfect suburban plots facing the broad empty street. Pefley grew up in a world more akin to his back yard. The son of a farmer on the American River, Pefley and his brother came of age in the harsh world of Depression-era farming in the San Joaquin Valley. "We were the hired hands," he says, "cleaning the chicken houses, drying fruit." The boys worked every day in the summers from 6am to noon, and then they headed to the nearby American River for afternoons spent fishing and swimming and whatever else they could fit in before dinner time. Early on, Pefley knew that he did not want to farm. He went to college, joined the Air Force Reserve during the war. When he was going to junior college in the Central Valley, Pefley took up tennis and found he had to play at 6am to beat the heat. Then he visited the Bay Area. "Here you could play tennis any time of day. I thought, I'm going to stay here for the rest of my life, even if I have to starve." Pefley didn't starve. He got his graduate degree in mechanical engineering at Stanford, thanks to the GI Bill. Soon he landed a teaching job at Santa Clara University and began searching for a place to settle down. As a country boy, Pefley was a little suspicious of tract housing. "Henry Ford built a Model T for $10, but they were all black. Housing is the same way. It's a compromise. Mass-produced housing, if not done right, it looks like ticky tacky," he says, referring to the 1962 Malvina Reynolds song about the cheap disposable houses that were going up across the country. When Pefley came to Westwood, lots were already dug up, homes were rising from the dirt in all phases of completion. He and his father looked at the half-built houses and were sold. "Once I looked at the construction, I never had a moment of regret." But Pefley was nervous. He had grown up with such freedom as a kid--it seemed like the whole Central Valley was his. Now his two sons and daughter were going to grow up on this pie-shaped lot surrounded by nearly identical homes, hemmed in by streets and fences. To son Steve Pefley, growing up in the early 1960s, Westwood was hardly tamed. "When I was a kid, I used to climb over the back fence and go into the strawberry fields behind the house. It was like that all around Westwood; it was all orchards. It was a lot like living in a rural area with all the comforts and conveniences of suburbia," says the younger Pefley, who was born in Westwood in 1954 and still lives in the valley. Being a baby boomer meant that there were lots of other kids around. Nearly everyone in the neighborhood had two or three youngsters. Pefley never went to a school he couldn't walk to. And after school, kids hopped on their bikes and pedaled into a world of seemingly endless freedom. When Madeleine Schramm, who still lives near Westwood, was a kid, two years older than Steve Pefley, she used to sneak through his fence to go play in the open field and climb the oak tree behind his yard. "It was idyllic," she says. "Kids would take off in groups and go explore. Most of my neighbors were boys. We would hang out, explore fields, climb trees." BUT AS MUCH as the suburbs were a dreamy kids' world back then, the criticism of subdivisions like Westwood has been long and intense. The suburbs were blamed for the conformity and conservatism of the '50s and '60s. Liberal intellectuals saw Roosevelt-era Democrats move into suburbs and, within a few years, emerge as Eisenhower Republicans. Sprawl, auto dependence, the train wreck of American popular culture, nuclear families or their failure, racism, depression, anxiety and sexism--all of these ills at one time or another were attributed to the modest pastel boxes lining the broad streets of American suburbia. But before the rancorous criticism, the suburbs had a powerful booster. America's most renowned architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, was himself a son of the Burbs, living and working in Oak Park, in the posh outskirts of Chicago. Wright, who designed dozens of homes in Los Angeles, watched the L.A. basin fill up with mile after mile of subdivision. He had grand plans for communities like Westwood. Just two years after Bohannon built his first homes, Wright published an article in Architectural Record titled "Broadacre City: A New Community Plan." Though infused with socialist ideals that included land redistribution and government-allocated lots and planning, Wright put out a pitch for a world much like the one that Schramm remembers. Housing developments surrounded by farms, schools within walking distance. Local industries like those that had begun to locate in Santa Clara were central to Wright's plan. And again, the ligaments holding it all together were highways traveled by the cars that every family would have. Wright was so car-obsessed that he imagined home size would be measured by the number of cars a family owned: the one-, two- or three-car home. Markets and cultural centers, he thought, would spring up at the busiest intersections, though he probably had something a little nicer in mind than strip malls. But the world Wright envisioned poked its head through the surface of the American landscape only briefly. Those ideals, and the balanced mix of rural and suburban, industrial and cultural, were thrown out decades ago for market-driven rapid development. But today, with more emphasis being placed on community, the environment and easing commutes, Wright's Broadacre City may once again have a chance. But it has long appeared as if this suburb, like others across the valley, was heading somewhere else, beyond Wright's socialist suburban utopia.

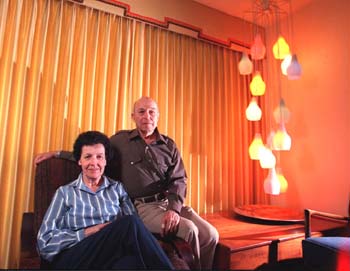

The Good Life: When Bert and Helen Martin moved into their home in Santa Clara's Westwood subdivision, they were in the middle of a prune orchard. Their neighbors, they say, are like family. WHEN SAN TOMAS Expressway was built, Schramm's favorite stream that she biked to with her friends was diverted and paved over, taken away as if by divine decree. Then the field went. "They took away our field. We would stand there every day and watch the houses going up. Little by little our world got smaller." As her world shrank, Schramm spent more time playing in the park that Bohannon built with the development. On the way home from the Westwood school, also built by Bohannon, kids would stop at the park to hang out. With a 10-cent deposit, they could use the arts and crafts supplies. No one worried about leaving their children there. The patch of green surrounding the swing sets at the corner of Rosita and Los Padres became a second home to Schramm. "I joked with my brother that they should have named the park after me," she says. But instead, by the end of the Vietnam War, the park would be named after him, Everett Alvarez Jr. Everett Alvarez was 10 years older than his sister. He grew up when the family lived in Salinas and was in college by the time they moved to Santa Clara. Though he visited home a lot, he only lived there for a year or so until he joined the Navy after college. "I remember being tickled when he became a pilot," says Martin, who served in the Navy during World War II. "Anyone who was in the Navy and was flying was all right by me." In 1964, Alvarez got shot down over Vietnam, becoming the first U.S. pilot to be taken prisoner. Eight years later he was released. When Martin heard about the torture that his neighbor's son endured, he was moved. "I wondered if I could stand up through that ordeal, having my wrists tied behind my back and hung until my shoulder was dislocated. That takes a kind of inner stamina, an inner strength that sets you apart from other people." While he was held captive during the 1960s, Alvarez's plight in Vietnam shook the neighborhood. "I lived across the street from the Alvarez family," Steve Pefley says. "I saw a family go from being totally normal to totally disintegrating. It just shows you how screwed up things can get. Everett's older sister became a peace activist, the parents got divorced, everything became unglued." Pefley saw friends go to Vietnam, never to return. Kids began doing drugs. The world split open, and things changed irrevocably. In those decades, more and more homes piled up on the horizon around Westwood. Increasingly identical houses stacked one on top of the other spread across the valley floor as the economy exploded, driven first by the Vietnam War and later by the rise of the personal computer. There were more jobs, more housing, more shopping, more cars, more freeways. More. "Suburbs are a waste of land and a waste of energy. Spread out like that, people drive their cars more, increasing air pollution," says Michael Southworth, a professor of city and regional planning at UC-Berkeley. The evils of suburbs are well-chronicled and rarely disputed, even by those who live there. But still more than half of all Americans live in the suburbs. The new Westwoods are rising in Modesto, Tracy, Hollister, spreading to areas that just five years ago were agricultural strongholds. While unplanned sprawl centered around another identical mall or near a convenient freeway exit has marked some of the most obvious development in the past decades, a change may be on the horizon. Today, communities are supporting slower growth. Ideas like infill development and greenbelts are no longer just words buried in Sierra Club policy directives; today they are city government agenda items and ballot initiatives. Communities, designed as little more than parking spaces with a bedroom attached, are trying to draw industry, trying to evolve into something closer to what Frank Lloyd Wright envisioned. Here in Silicon Valley, San Jose's Redevelopment Agency has dumped hundred of millions of dollars into downtown amenities and housing, begging businesses and people to try urban living in a valley as thick with subdivisions as it once was with fruit trees. What the people really want seems to be a house with a yard, some place to really call their own, even if it has a fence around it and looks a lot like the other houses on the block. Retro trends, like lounge music, the swing revival and a fascination with kitsch Americana, also look back to life in places like Westwood. "There is a movement towards recalling the most beautiful designs, everything from the 1950s and '60s," says V. Vale, publisher of V/Search Publications, which focus on emerging cultural trends. The optimism and innocence of the 1950s has an appeal to today's twentysomethings, he says. Though many of them are not moving into the Burbs to raise families like the Martins, they are picking up bits and pieces of that culture. The Burbs are truly American. They are headless, decentralized places that don't rely on any one city or town. The traffic snarls equally in all directions. It is perhaps no surprise that the Internet, itself a sprawl of global decentralization, should find its creative home in the vast suburban plain of Silicon Valley. If the web is democratic because by its nature it rejects hierarchy, suburbs were its precursor. The valley's vast network of office parks, manufacturing centers and subdivisions is ultimately democratic, haphazard, increasingly egalitarian, and culturally and ethnically diverse. For all their faults, the Burbs are, at their core, American. ON A COOL GRAY MORNING, Vern Wyman takes a break from packing and stops for a moment to look at the green manicured front lawns outside his picture window. The living room is empty now, except for the furniture. "It's amazing," says Vern, a tall, wiry-thin 72-year-old, as he leans over the bright yellow love seat. "They've got these big strips of plastic they just wrap around the furniture and then they throw it on the truck, just like that," he says, motioning with his arms around the chair, breathing in the emptiness of the living room that had been so full for 47 years. The movers are coming tomorrow at 8:30am. Back in 1951, Vern and Margaret, then in their 20s, watched this house rise up out of the orchard. The house was a gift from Margaret's mother, who worked as Bohannon's secretary. Five years later, when the young couple had more money, the Wymans bought the house back from her. Now they are moving to live closer to their son in Pollock Pines, in the Sierra foothills. In the yard, Vern and Margaret look around at the patio, the pool the double lot so big that it has two fences, one around the pool and one around the border of the property, leaving a long awkward walkway and a square of unkempt yard hidden behind the fence. It's where the kids would go and shoot bow and arrows, Vern explains. "This home and yard has consumed most of my time," Vern says. "Now I'll have time to be involved with more things." He looks at the cement patio he poured in the yard, the flower beds and the shrubs he planted and trimmed. "I worked on this for 46 years." "We'll miss it. We've shed a few tears," says Margaret. "We've cried more than once," Vern adds. They have that kind of seamless conversation that some couples get after decades together--they finish each other's thoughts without even realizing it. Vern and Margaret point to the flowers the new owner has already put in, small bursts of pink and blue pushing up against the fresh dirt. She has a daughter, like the new neighbors on either side. Before all the packing began, the Wymans had a party for the new owner, to introduce her to the neighborhood. Everyone got along well, they say, especially the girls. They seemed to love the vast expanse of the Wymans' yard, the pool, the secret place behind the fence. "I think," says Vern with a satisfied glance around the property, "they'll get along just fine here." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the June 3-9, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.